Main pump delivering water to Ramallah

Pumping station, Ein Samia well field

Ein Samia

Excerpts from my journal during a three month journey of photographic discovery in the Land of Troubles

Special thanks to Fareed Tamallah for this lead, and to Malek Baya who guided and hosted me.

July 26 & 27, 2009, Sunday & Monday, Ramallah Friends School apartment:

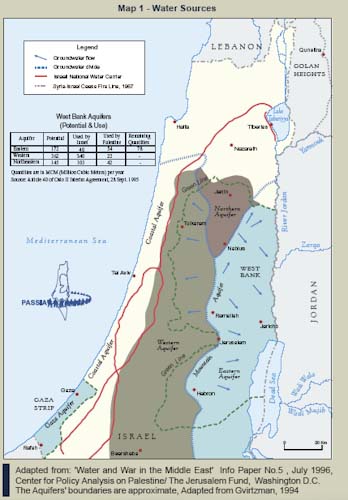

A story about a water source north of Ramallah, in the valley of Ein Samia, 20 km northeast of Ramallah: my friend, Fareed had told me about Malek Baya, who lives north of Ramallah in a village, Kufur Malek, near the source of a considerable amount of water supplying Ramallah. It is one of the few Palestinian controlled sources. This is the furthest in a long line of villages that seem water rich, compared with some other regions of the West Bank. Malek picked me up at Manarah Square (after he first suggested I take a taxi out, which would have been confusing and expensive), his little white car loaded with the rest of his family, wife, 2 daughters, one an infant, and two sons, one an invalid from a fall, brain damaged perhaps for life, unable to speak or move much, we headed north.

Malek Baya

First along the “Ancient Route” that Adel had told us about on the Nablus tour, the traditional route over the mountains north and south, connecting Syria with Egypt, but the Israelis had blocked this and so we left it for smaller roads. First thru the village of Ein Sinya where we observed what may have been an ancient waterway, now dry (partly because of the season), carrying a putrid smelling sewage viaduct, bordered by green fields, some with curious white hoops covering plants. We found an old building which Malek claimed once housed a flourmill, now used as stables for sheep. Also a spring with a man filling up jugs. He did not want his photo made.

Spring, Dura Al Kre

Further north to Dura Al Kre, another well watered village, with a similar configuration of waterway, but this time with numerous springs up about 5 meters from the lowest point. Water drained from splits in the limestone ridge and was collected in various ways, the overflow held in a cistern and later flowed to the fields. Debris floated in the cistern but the men told Malek that they periodically cleaned this out. A woman had gathered water and was carrying it on her head. They showed us another site further up which had been piped, the system paid for by a wealthy Palestinian-American who returned every summer. Apparently all of this infrastructure was built and paid for by local villagers and friends, not a government entity or non-governmental organization.

They told us that during the summer the main water supply thru pipes is turned off by some regional authority, presumably Mekerot, the Israeli company which supplies—at, the villagers claim, inflated fees and capriciously—much Palestinian water (Palestine’s own water, by the way, stolen as some believe since the aquifer lies beneath the West Bank), and then the village relies on these springs. Which also can slow down but apparently never stop. People have to lug this water.

Spring water, Ein Sinya

My constant question was how this region looked hundreds or maybe even a mere 20 years ago, before global climate change and before the expansion of the population? From the geological record it appears much water once flowed thru here, perhaps gradually diminishing over millennia. I have to remember—and this requires a fertile imagination—that this entire region was once beneath a vast sea or ocean, and the limestone is the deposit of the aquatic life once flourishing here. It is organic rock.

Water to Ramallah

Finally, Malek’s village, Kufur Malek (odd that his first name is his village’s last name), and after resting and eating, a trip to our target, Ein Samia, site of the well field supplying some of Ramallah’s water. His wife served muqlubah, upside down casserole, with chicken, potatoes, carrots, onions, and rice, with a few skinny noodles thrown in. Along with salad, sweet drinks, water, and later, after we’d returned from the main excursion, ice cream. A feast in many ways.

While waiting to leave for Ein Samia, Malek’s uncle, also father in law (he married his first cousin, after medical tests which found their genetic profiles safe for marriage, a love marriage, not arranged, he was quick to point out, 9 years, and they seem very happy together) played with the youngest, a mere babe in arms, another lovely child in this family of extraordinary and precious people. I played minimally with the 5-year-old daughter (5 next November), lending her my mechanical pencil with which to draw or write, after she’d showed me her coloring book that she and her older brother had colored. I raved about her coloring, solidifying our relationship. Who can resist strong, heartfelt praise? While playing I made a series of photos of her, moving the camera down low, at times using my Canon’s S3 fold out screen, and finding later a few might show her radiant spirit. There is something very special about this child, as is true for the entire family.

Daughter of Malek Baya and his wife

And about the uncle who I learned is a jolly and robust 69-year-old widower. At first when I noted our age equivalence, I thought, he looks very old. Do I look this old? How creaky is he? As creaky as I feel? Not at all, he is nimble, agile, truly bouncy where I, by contrast, despite X’s belief that I am bouncy, feel like and might be creaking to a halt, a permanent halt. I’ve never felt so old. (Tho today I feel younger. Is it the food supplements? The night’s rest? The beautiful people in and around Ramallah?)

OK, enough domestic verbiage, let’s keep on point: hydropolitics. Uncle, Malek and I bundled into the car and drove off. Up and up some more. First past a limestone cutting facility spilling chips along the road. The beginning of viewing the long pipe line between the source at Ein Samia and its destination, my mouth in Ramallah—and that of about 25,000 other thirsty mouths waiting to be watered.

What is the story of the line’s construction? Dates back to the early 1960s, after electrification of the region but not Malek’s village, and during the Jordanian occupation. If I have the story from Malke correct, the brother of King Hussein of Jordan, a prince, met and loved the beautiful wife of the Ramallah mayor. Prince abducted and raped the woman, she committed suicide in despair and shame. Ramallahans were outraged. King did not punish his wrongful brother but as penance paid for the installation of the water system, including the electric line needed to power the pumps.

Israeli placed road block

A long diversion here (with some legalese thrown in), since I’ve not been able to corroborate the story of the Jordanian prince, what follows is the official version as promulgated by the Jerusalem Water Undertaking (JWU), the agency responsible for this system:

Until late 1950s, the population of Ramallah and Al-Bireh cities depended almost entirely on cisterns for drinking water with the exception of a few local springs. Following the war of 1948 and the resulting influx of Palestinian refugees into the area, the need to increase the water supply in the region became vital. Thus, Ramallah and Al-Bireh Water Company was established to deal with this burden.

The new company planned to draw on Ein-Fara springs northeast of Jerusalem and succeeded in concluding an agreement with Arab East Jerusalem Municipality. A distribution network and a main pipeline were constructed for the purpose of conveying water from Jerusalem to the Ramallah and Al-Bireh area. Though, the limited quantities of water were insufficient for the served population.

In 1963, the Jordanian Government concluded an agreement with the International Development Agency (IDA) for a loan of US$ 3.5 millions to develop drinking water projects in some parts of the Kingdom. The Government decided to utilize the groundwater resources in Ein-Samia wellfield, 20 km northeast of Ramallah, and initiated construction in what later became known as the Ein-Samia Water Project.

Pursuant to the respective agreement between the Jordanian government and IDA, the founding law of JWU was issued in 1966 with a mandate to develop new water resources and control all water projects in the area with the responsibility of providing the population with potable water. According to this law, JWU was established as a non-profit, independent, civil organization run by a Board of Directors including representatives from the three main municipalities in the area; Ramallah, Al-Bireh and Deir Dibwan, in addition to a representative from Kufr Malik village and an assigned Official from the Government.

Since 1967 occupation, the Israeli Military Authorities subjected all works and projects pertinent to water and water resources to its direct control through the Military Order No. 92/1967.

Illegal (under international law and UN resolutions) Israeli settlement/colony

The mentioned order prevented any organization or undertaking from the execution of any work connected to management, maintenance and development of water services or resources without obtaining prior approvals and licenses from these Authorities.

In 1982, the Israeli Occupation Authorities dissolved the city councils of Ramallah and Al-Bireh cities, thus, disabling JWU Board of Directors from performing its duties. For five years and without the Board of Directors, JWU top management met the challenge and made all daily and strategic decisions to achieve the Undertaking‘s Mission.

At the end of 1987, the mass public Uprising Intifada started in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. The whole political, social and financial situation in the area changed. Many people were put out of work, thus, putting an extra burden on JWU. Through these tough days of Intifada, the Undertaking managed to survive.

In the wake of the rule of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), The Palestinian Water Authority (PWA) was established in 1995 assuming the regulation powers of the water sector in Palestine. In 1996, the Government representative in the Board of Directors of JWU was invited to join the Board for the first time since 1967.

Nothing about the Jordanian prince, true or false, Malek says true.

So hydrologically the water has accumulated in a low place on its way to the Jericho valley. This is in a wide wadi that in the old days might have flowed regularly with much water. Wells, pumps, and the water is brought to the surface. Then it has to be pumped over the hills and up to Ramallah which is not only about 20 km distant but 500 meters higher. Should electricity fail—and Malek told me it very rarely does—that’s the end of this source of water. Or should the aquifer deplete further, as it is doing, and should Israeli restrictions continue to apply about well depth, so long water. Or should the water become polluted from sewage and farming chemicals, a real possibility, the end of this source of water. Likewise the vulnerability of the pipes themselves, which would be catastrophic if violence again hit this region. The pipeline could be easily destroyed by Israeli incursions. I’m surprised they did not attack it during the 2002 invasions, if they didn’t. This remains a constant threat.

This water, this life, is precarious.

Grain mill from the Roman period

So back in the car, higher and higher, road narrower and narrower. The road, uncle tells us, was built during the Jordanian period, between 1948 and 1967. Malek told me that now hikers regularly traverse this same region, Ramallah to Jericho. I might try this sometime. Jericho is only about 30 km from Ein Samia, and maybe 40 km from Ramallah itself. Distances are shockingly short here, yet long because of the matrix of control, the occupation.

Uncle told me about the quarry pit which is clearly on Palestinian land but often the Israelis prevent them from using it or if they allow use charge them a fee. Where else in the world would this be allowed?

Uncle is a study in traditional Palestinian life. His trade is stone cutting; he also sells cut stone and gardens. He is not retired, tho at retirement age, 69, one year older than me. He will not leave the village for the city, should the family decide to move to Ramallah permanently. (Malek, with a flat in Ramallah closer to his job as software engineer and less subject to closures and road obstructions, wishes to eventually move back to the village, when conditions ease more.) Uncle cares for the infant and the children, obviously good with them as I try to show in my photos. He grew up when this land had no road access to the fields in Ein Samia where his father farmed. So he’d ride a donkey to bring the lunch food. He knows the plants, picked for us early figs. He also seems expert in the history of the region, overjoyed to find someone like me so interested in learning. And then when Malek and I had had enough and wished to return to Malek’s village, uncle wanted to go further and did, lingering in fields that must bring back many memories. As I’ve written earlier, tho he’s one year older than me, he is much more agile and perhaps stronger.

Malek’s uncle & father in law

His wife died 6 years ago and Malek told me they’re trying to find him a new wife. Is he lonely? Does he enjoy life at the homestead when the rest of the family is in Ramallah?

I wonder about how the family is changed by the presence of the 7-year-old infirm boy. He’d fallen from a swing or see saw, injuring his brain, and because of the limited medical resources will probably live out his years in this condition. Can’t speak but can understand speech. Can barely move. Cries when his siblings go off to school or play. They treat him with respect. His body is contorted. I wished to photograph him, especially with siblings and mother, but never found the opportunity. Maybe another time, should we meet again. This family also is a story in itself. A marker of the current occupation.

While waiting to go, for the rest of the family to pack, Malek toured me thru part of the village. Very hilly, pretty, many new homes, and this being summer, the wedding season. Several each week. All in the village of about 3000 are invited, but only the core element will be fed.

Lights were coming on as we departed, and just as we left the driveway a group of 3 young girls met us and chatted. This gave me one last opportunity to photograph the village, the lights on the horizon.

And this might end my lengthy account of water and life north of Ramallah. For now.

Courtesy of the Internet

LINKS:

Skip … great posting, although I’ll admit that I skimmed the water hydraulics in favor the people.

You give a strong portrait of the family … especially the uncle. And I really like the photo of him with the infant in arms.

So the “domestic verbiage” is what caught my attention. In my case, I guess H20 hydraulics loses out to people.

And yet I know that the former is critical to the latter … even if it isn’t a compelling subject.

… Chuck

LikeLike

chuck, thanks for your honest reflection.

i believe you might speak for many, even myself at times. each can chose what is focused on. i’m fascinated by water, water is a pivotal issue in palestine, israel, the middle east, the entire planet, so my challenge is to discover a palatable way to investigate and present. there is a certain beauty in pipes, pumps, wells, spring, water for sure, and i hope to convey some of that. intertwining with the beauty is the horror, or potential horror of depletion, pollution, and illegal and immoral and unjust distribution of resources.

see you on the other side, dear friend.

LikeLike

Keep up the great posts, Skip!

LikeLike